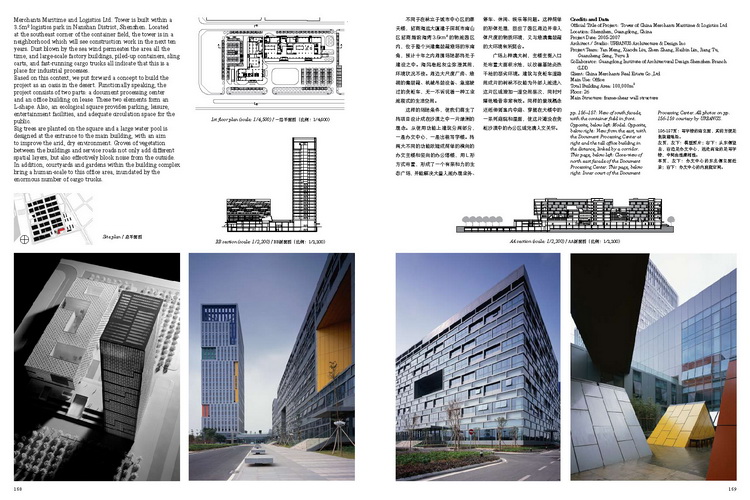

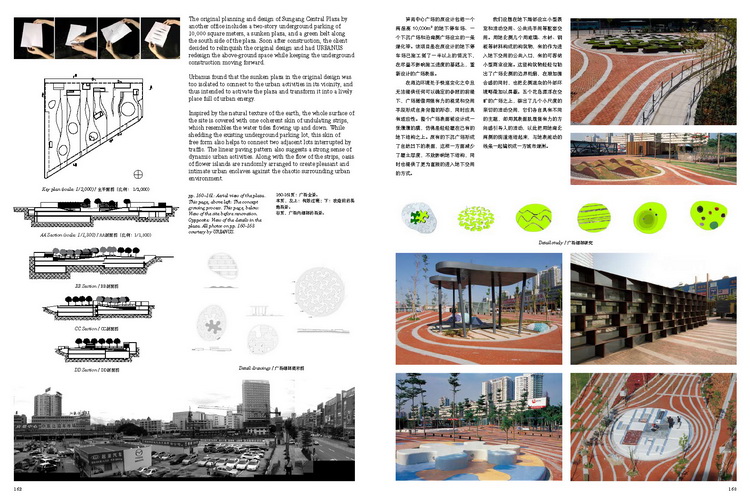

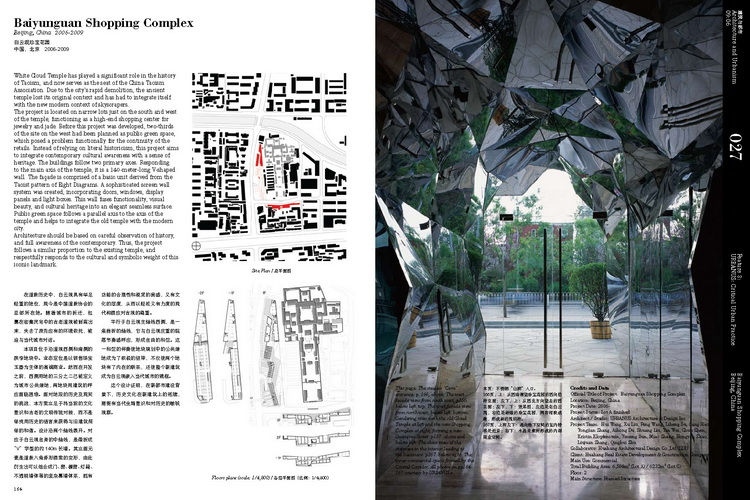

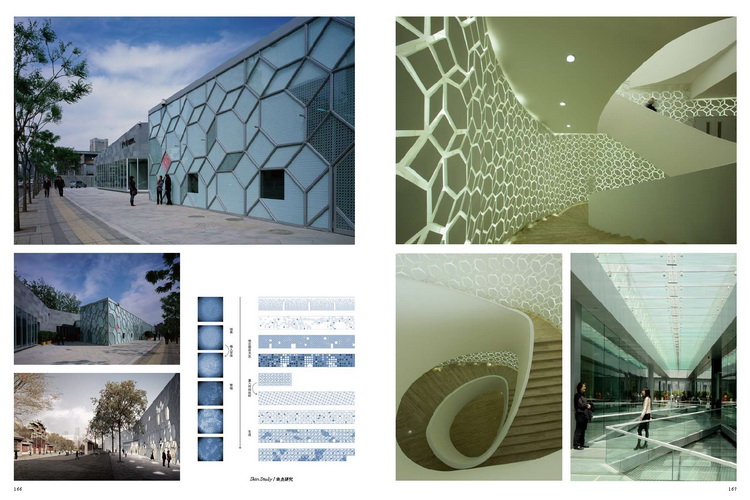

Feature: URBANUS-Critical Urban Practice / Interview: URBANUS-Building for Cities p142-179

Critical Urban Practice in China (Learning from Shenzhen)

Laurence Liauw Wie Wu

Urbanization as agenda and material culture in China

The material culture of Chinese cities is founded upon urban conditions that are at the same time general and specific, formal and informal, small and large. This complexity requires urban research to understand conditions that are seemingly discontinuous and incoherent, therefore preparing practitioners to engage with public domain critically through an urban practice mechanism, and avoid architecture which may be reduced to regressive representations or abstract compositions.

China’s high urbanization rate over the past 30 years when 400 million have moved to cities from rural areas has created a unique and unconventional urban culture, unlike anything the world has seen before – producing what Koolhaas called ‘generic cities’, with Chinese architects producing the greatest volume of buildings in the world. Before the 1990s, most Chinese architects were part of large state-controlled Design Institutes. Architects become by-products and facilitators of this upheaval in society. But after the 1990s, a few critical architects were mainly focused on cultural, tectonic or ideological concerns.

And about 10 years ago, confronting the ‘dirty realism’ of China’s contemporary city culture, Xiaodu Liu, Yan Meng and Hui Wang created Urbanus, and choose the “urban” as the start point of their practice. They see the evolving contemporary Chinese city is “a source of pain and evil, as well as endless (delirious) joy.” Cities being the ‘face of China’ today form the material culture of the country under development, architecture literally manifesting a society in transition. The 1990s privatization of Chinese cities (and housing) resulted in sustained urbanization in China. Society transformed by rapid urbanization is mediated through new urban architecture. The social practice of architecture ideologically formed in previous eras has given way to capitalist development with ‘Chinese characteristics’. For Urbanus, the city has become both a field of study and operation, and architectural practice becomes an instrumental projective urban device for effecting critical urban change. Urbanus’ projects can be classified into either ‘urban engagement’ (urban strategies enabling architecture to discover opportunities of the city neglected by others) or ‘urban infill’ (urban voids that can activate urban regeneration). 3 critical principles underpin their practice: restoring urbanity within climate of rapid market-driven development and irresponsible urbanism; conducting innovative and critical praxis with social agenda, against conventional repetitive practice; and converting ordinary programs into active urban devices that can energize urban life.

‘Hai Gui’ : Education of a Chinese architect China’s educational policy set into motion in the 1980s .of sending talented post-graduate students to study abroad, brought back new knowledge and perspectives to transform China. Overseas educated returnees known as ‘hai gui’ have largely been responsible for China’s globalization. Urbanus founding partners Xiaodu Liu, Yan Meng and Hui Wang, became one of the first generation of ‘hai-gui’ returning in 1999 at a time when China’s progressive architecture was still under development. Gradual shifts in design competitiveness

from dominant huge State-owned Local Design Institutes to atelier-style Studio practices represent a search for design quality. Urbanus’ self-imposed culture of seeking opportunity, experimentation with a frontier mindset, created an architectural lab and platform embracing both design and research practice.

Learning from Shenzhen as urban lab

Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) was Deng Xiaoping’s brainchild in 1978, representing the ‘Chinese Miracle’ since it was a city ‘created from zero’ by both Chinese political ideology and international market mechanisms. Shenzhen has led China’s recent urbanization boom, with 27% economic growth on average, and population expanding from 30,000 to now well over 12 million. This radical transformation and its urban culture attracted Urbanus to setup there originally.

Shenzhen’s success and ability to grow and attract new urban populations have made it a development role model spreading to other Chinese cities and also beyond China. An urban ‘Petridish’ created tabula rasa as an Urban Lab, Shenzhen is not the same as other PRD cities, nor Guangzhou, Shanghai or Beijing.

Shenzhen is totally free from physical constraints and ‘cultural limitation’, enabling it to constantly accommodate the most radical experiments in urbanism and architecture. This spirit of‘fertile emptiness in the void’ makes all things possible. In recent years due to planning innovations, media exposure, international biennale exhibitions and radical projects built, elite scholars and practitioners have paid more serious attention to the urban condition of Shenzhen. In 2008 Shenzhen was awarded UNESCO status ‘City of Design’. This is a reversal of conventional cultural influence dominated by ‘cultivated historical cities’ such as Beijing and Shanghai. Within this fertile environment, both virus and new innovations of the new city can grow freely. Learning from Shenzhen is unlike Learning from Las Vegas, but could have the same culture impact eventually.

Development Phase 1: Genesis in Shenzhen (1999- 2003)

During the early years Urbanus had the opportunity to swiftly build in Shenzhen a range of conventional urban types (except the first plazas and urban park). It had designed over 170 projects in its first 7 years, of varying scales and complexity. Works can be classified into several urban categories – Urban Intervention, Urban Edges, Urban Regeneration, Urban Anchors, Urban Landmark Urban Public Space and Urban R&D. Significant early commissions such included Diwang Urban Park I and II, Public Art Plaza. The practice subsequently designed and built more typical commercial projects such as sales offices (Grand Constellation), mass housing (Dameisha

XinHaiJiaLan Housing) and commercial high-rises (Shenzhen Metro Tower) whilst also pursuing public projects through design competitions. They eventually won the landmark commission to design the new Shenzhen Planning Bureau Headquarters, which to this day remains a symbol and place of planning power and architectural discourse in Shenzhen.

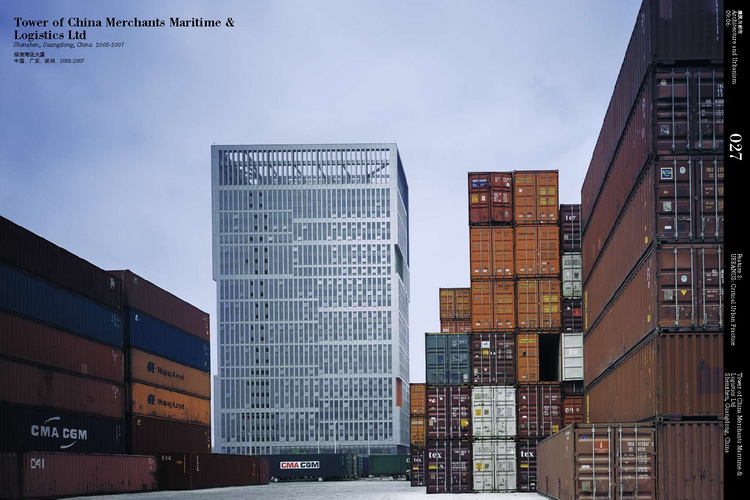

Projects Phase 2: Shifting cities culture design experimentation (2003 – 2007)

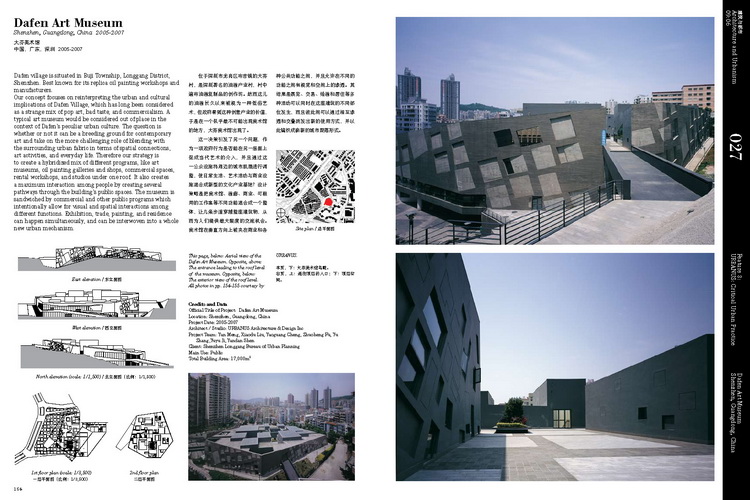

Whilst competition wins and commissions flourished in Shenzhen for the practice after the first 4 years, Urbanus decided to expand from Shenzhen up to Beijing in 2003 setting up a branch of the practice. Beijing and Northern parts of China were developing rapidly after the 2008 Olympics were announced, and new economic development zones were setup such as those in Tianjin. Urbanus’ approach worked differently in Beijing as historical cities fabric and culture were different there. Cultural, historical and political issues became more important in how projects were developed. Scarcity of land and natural resources, growing concern for old fabric of cities, and creative industry development led to a period of experimental design and new use of building design technology for Urbanus after 2003. Significant milestones included projects for Beijing CCTV media park competition, OCT East factory district Shenzhen, and becoming the only Chinese practice to win a major Olympic Venue for the building Digital Beijing. Numerous urban design competition projects in 2nd tier cities outside of Beijing resulted in commissions in Tianjin, and later Tangshan. This was also a period of urban research into critical issues such as Village-in-City phenomenon in Shenzhen, which resulted in a commission to build the Dafen Art Museum. The opportunity to explore possibilities of new society and urban life through architectural design research, reflection and critical engagement characterizes this period of practice.

Projection Phase 3: Addressing issues larger than architecture (2006-2009)

A new phase of the Urbanus as a critical practice is emerging from recent projects that could be speculatively characterized as projective ‘Ideas for the City’ rather than being mere building projects. Their earlier urban research have informed the production of new architecture, which could be seen as some kind of new urban types and prototype processes. This approach extends the future ambition and potential of Urbanus to be instrumental in transforming future urban China through a critical and projective urban practice.

Five exemplary projects in the recent phase of the past 10 years

1. Tangshan Exhibition Park: Adaptive reuse Tangshan Exhibition Park addresses public urban identity within a typical generic second tier city within an expiring post-industrial and banal setting. The project makes use of valuable resource of existing city fabric and place. It promotes local culture and heritage, through adaptive reuse, conservation of urban memories. Aside from extending a city’s memory, it helps to reinforce an urban confidence in this second tier industrial city near Tianjin. Now actively used by citizens and government officials, the project also preserves urban spirit, after the memory of Tangshan 1976 Great Earthquake. Building renovation and new designs complement the natural landscape at hillside and responds by incorporating natural elements of water, light, ventilation and local materials with contemporary interpretation. Six new additions plus four existing granaries built during the Japanese-occupation era, and two warehouses built after the Earthquake are conserved with new museum programs and new building related to urban planning. The museum park’s historical content gives residents an opportunity to understand the city’s past that has very few physical traces left, and a new place for daily leisure.

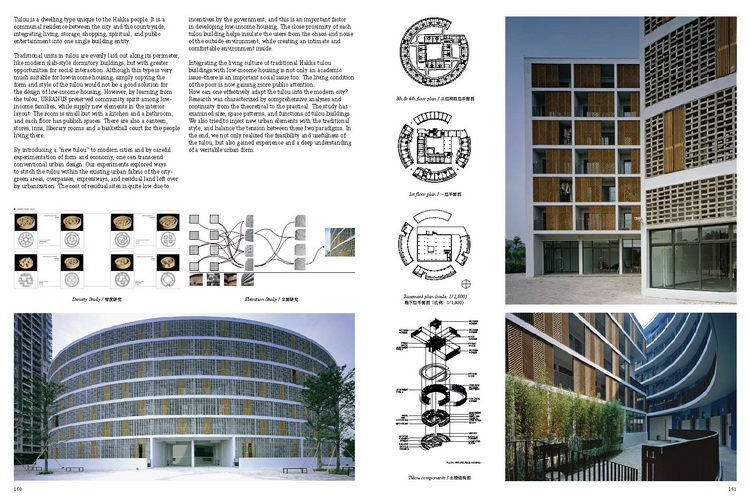

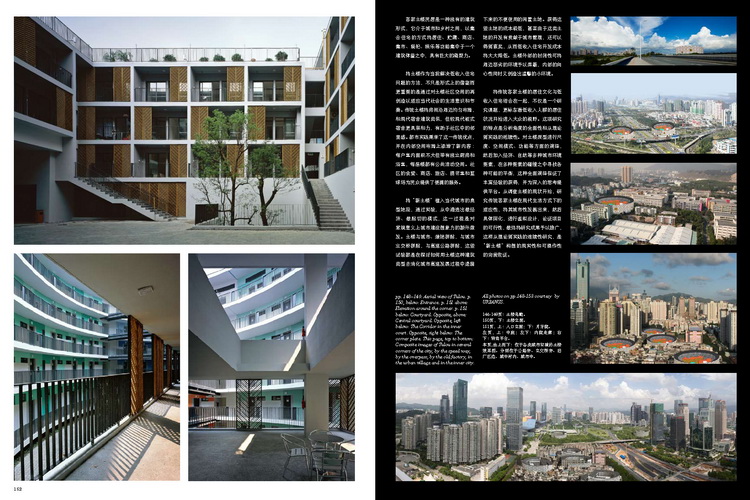

2. Tulou Commune: New type Since the 1998 Housing Reforms that abolished Government provision social housing and introduced privatization of housing, affordable housing has been in shortage for China’s ‘floating populations’ of over 150 million migrant workers. Urbanus and their developer client Vanke have adapted the round vernacular Tulou typology to Chinese contemporary city fabric and lifestyle needs. Different typological variations (O-type, E-type, C-Type etc) of the Tulou collective housing type that could adapt to different parts of cities, as urban infill, community catalyst, highway landmark, or inner city regenerator. When more affordable housing is urgently needed, improved quality of life for non-registered skilled migrant workers may encourage them to settle down in cities, and upgrade China’s urbanization process. If new Tulou Chinese type with variations and not mass produced model could spread to other cities, it may herald a new Utopian Age of ‘Peoples Commune’.

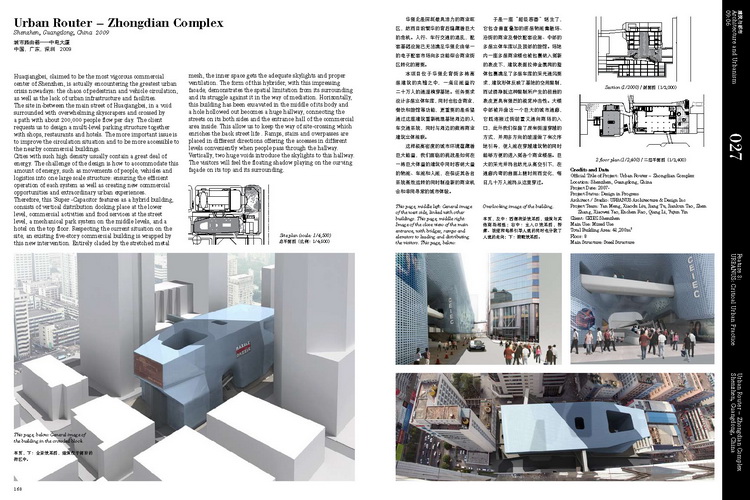

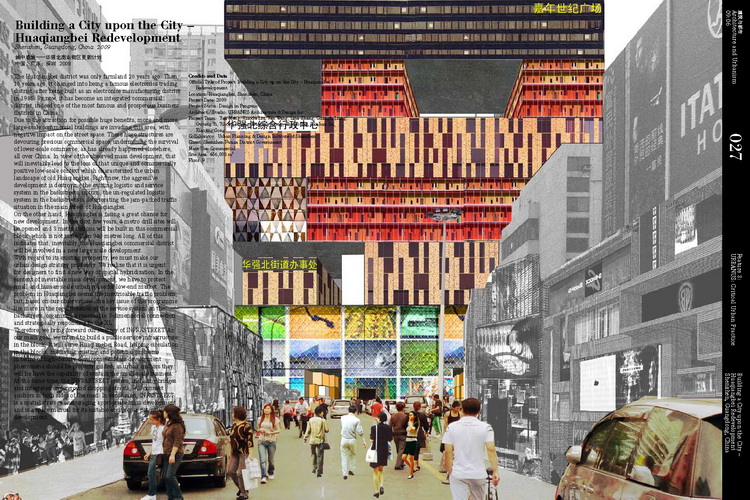

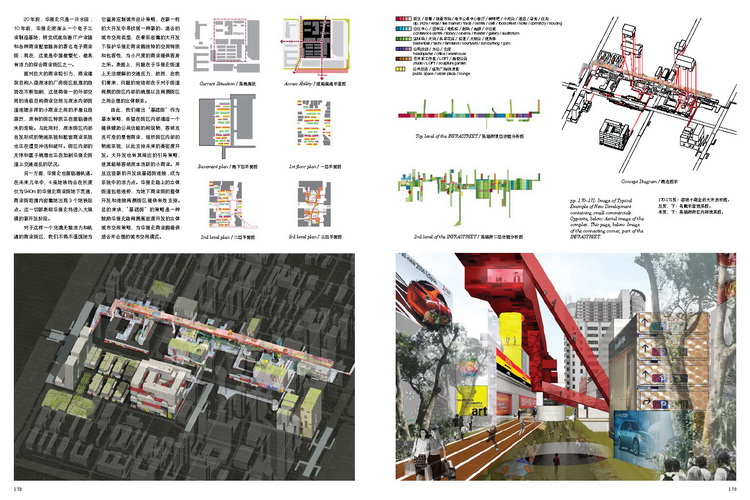

3. Huaqiangbei: Urban design Huaqiangbei 3D Street is an important urban design in Shenzhen aiming to transform the busiest 1,000m long street and commercial district into ‘the 3rd most important commercial street’ in China after Wangfujing and Najingxilu. Generating 8% of Shenzhen’s entire GDP, Huaqiangbei area attracts over 600,000 visitors at peak periods. Huaqiangbei is a chaotic mix of electronics mixed with ladies fashion and wide leisure boulevard. Two new subway lines intersection here will increase future density both in people and programs – a ‘culture of congestion’ will prevail. Urbanus research identified that the success of Huaqiangbei depended on the ‘backstreet mixed use culture’ so typical of many Asian cities such as Hong Kong, Seoul and Tokyo. Weaving multiple 3D interconnecting program flow corridors from main street frontage to backstreets. Publicprivate mix programs such as retail, flea markets, conference, cinema, gallery, library, sports, offices, LOFT, dormitory and housing would all activate public life and attractiveness through landmark social condenser buildings and infrastreet corridors.

4. Qianhaiwan MTR Station: Infrastruction Large scale infrastructural projects are now entering Urbanus’ portfolio. Under design development in Shenzhen is the Development Plan & Urban Design of Qianhaiwan Metro Carshops. Occupying enormous floor areas of 1,420,000m2 with a site area of 55.9ha, the project will include retail, offices, cinema, LOFT, exhibition halls, kindergartens, and leisure clubs. The project is part of Shezhen Metro 2015 expansion program. The site is at a major interchange junction of entire Shenzhen city linking new East-West with North-South lines. Flow, speed, program, scale and railway track geometries are amalgamated to form linear densities adjacent to train tracks. Other major infrastructural projects being planned in Shenzhen will closely link it with Hong Kong as a Double Core Global City.

5 . Gongming District: Urban research Urbanus latest collaborative urban research project (with this essays author) involves investigation at the scale whole of city district and finding its inherent urban character for adaptation and transformation of the new town centre. Gongming town center area is more than 225ha, within Shenzhen SEZ next to the newly masterplanned high tech and sustainable Guangming‘New Radiant City’. An adaptive parametric approach to urban research aims to analyze and discover systemic character, friction, opportunities, conflicts and gaps for future transformation. To operate at this vast scale, projects should be strategic at large scale and instrumental at smaller human scale in transforming the city. Questions about how to deal with a generic Chinese city and create specificity without erasure or artificially importing new urban cultures could be tested through this research that could be extended to many other similar 3rd tier generic towns in China.

The social project and avant-garde Urbanus ask the question “could critical thinking enable Chinese architecture to develop an idiom based on the specificity of contemporary Chinese (urban) culture?” They have setup an alternative discourse for architecture in a country often obsessed with its painful historical past and sometimes intellectually exclusive more than inclusive. China may not be only importing architectural talent, and is already exporting its own brand of urbanism In times of great urban transformation, this form of critical practice could be the calling of an avant-garde (like CIAM, Archigram generation, New York Five and the Metabolists). The word ‘avant-garde’ means breaking new ground, leaving the familiar, and pushing for progress through radical means until a paradigm shift emerges. Urbanus with their persistent belief for a return to the ‘Social as a Project’ and creation of architectural platforms of public engagement could potentially lead the charge. Architecture in China has improved because of media, and the city also has become one of China’s newest communication mediums. Urbanus could be seen to be both ‘Made in China’ and ‘Making China’.

Critical urban practice what challenges lie ahead for evolving architects like Urbanus as demonstration of critical urban practice working in contemporary China? A few principles have been established. Firstly the Shenzhen-Beijing city culture axis is well established now by architects as both a source of thinking and production. Secondly that Chinese ‘hai gui’ ambitions for practice can be realized once cultural adaptations with new design techniques are applied to contemporary urban conditions. Thirdly that criticality in practice needs to be reflective, projective and instrumental over a period of say 10 years with experimental research required. The Western model of theorization followed by practice seems to be reversed here, with practice evolution influencing theory in China. Could these conditions eventually produce a Chinese avant-garde within the figure of The Chinese Architect? China’s position of influence is through example not rhetoric, and Urbanus being at the forefront of critical urban practice, needs to find ways to keep their edge and help nurture future generations of progressive architects at home and overseas.